Andrew Bailey, the Governor of the Bank of England, gave another of his excruciating speeches on economics yesterday.

You only had to read it to know how far adrift from reality he is. Start with this:

Monetary policy, in other words, works through the management of aggregate demand in the economy. Simply put, when inflation is too high, we increase bank rate to dampen demand; when inflation is too low, we reduce bank rate to boost demand.

The obvious question Bailey had to answer as a consequence is where is the evidence of excess demand? In a country with consumption flatlining and incomes falling there can be none. He obviously has not noticed that simple fact.

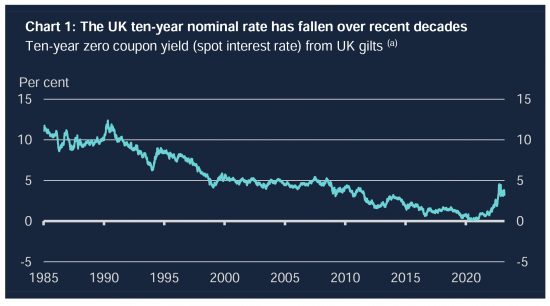

Instead, Bailey tried to justify this chart:

Bailey claimed that the aberrational uptick at the end of the chart, which is of course the result of his policy, could be explained as follows:

A good part of this decline can be explained by lower inflation itself. It reflects the success of inflation targeting in delivering low and stable inflation over long periods of time. Under inflation targeting, monetary policy makers act decisively to return inflation to target whenever shocks cause prices to rise or fall by too much. So even if inflation is now high, people can trust inflation to come back down to target. As a result, savers have come to demand a lower premium to compensate for expected inflation.

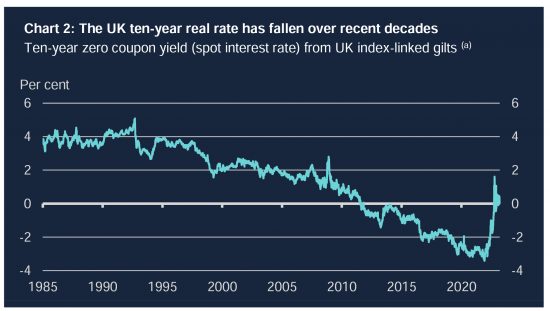

Very politely, this is drivel. The claim is that the Bank has been so good at targeting inflation the need for interest payments has faded away. His own next chart proves that is nonsense:

People did not give up on interest. Instead, rates went markedly negative from 2008 onwards. The trend was heavily downwards. The current policy he is promoting, in the absence of any explanation of its need based on there being no excess demand in the economy, is a blatant attempt to restore positive interest rates. The problem is that there is no evidence to suggest such rates are sustainable.

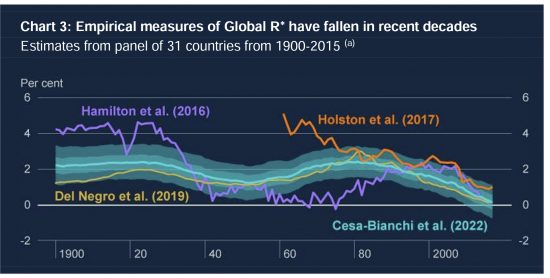

This is shown in his third chart, which refers to global average long term interest rates, where the persistent downward trend is seen since the onset of neoliberalism and the growth in inequality:

Bailey has a different explanation for this. He argues the downward trend is for two reasons. The first is that there are more old people in the UK. The second is that productivity in firms has fallen, especially since 2008. He said:

As people accumulate savings over their working life to fund their retirement, wealth in the economy increases as the age distribution shifts towards older cohorts.

As statements of the obvious go, this is first rate. This has always been true. What he said next is not true:

So ageing households have sought to lend more at a time when less productive firms have sought to borrow less. The only way to establish an equilibrium between the supply and demand in the market for investable funds – that is, to incentivise firms to invest this additional wealth into productive capital – has been for the price of those funds, the real interest rate, to fall.

This is nonsense for three reasons.

First, it suggests that markets set interest rates. But the whole premise of central bank regulation of monetary policy is that the central bank is able to do so. Bailey has to believe that this is true or his whole argument, and job, fails. He cannot make both arguments in the same speech: only one of them is true.

Second, the argument assumes that banks are intermediaries between savers and investors and that investment comes from saved funds. But the Bank of England admitted that this model of banking was not true in 2014. They admitted that it is credit that funds lending and so investment, and so saving. In that case, once again he cannot make an argument that the Bank knows is not true.

Third, he ignores the fact that savings have alternative uses, such as speculation. Financialised markets have not made their returns from investing: they have made money from speculating in money itself. Again, it is absurd that he does not acknowledge this fact.

The result is Bailey’s claims make no sense at all.

That said, he may be a little closer to the truth on productivity, where he said:

‘[F]ollowing the financial crisis, manufacturing productivity growth fell back sharply. This fall in manufacturing productivity is the main cause of the slowdown.

The reasons behind it are much debated – and productivity may be harder to measure in the modern economy where businesses invest as much in intangible capital, like software and branding, as in physical capital, like buildings and machinery. Measurement problems could be a big part of this. But much also points to structural change. Perhaps new ideas have become harder to come by, or perhaps technological innovation and specialisation have faded as globalisation slowed.’

I think he is right about measurement. He is also right about the shortage of ideas: there appear to be very few. There is nothing like the idea of the internet around now to transform the whole process of business and to transform markets as there was in the 90s and 00s. AI is not it, I am fairly sure.

But being partially right does not support his argument that business is not investing for this reason. It is not investing for three reasons.

The first is that there are bigger superficial returns to be made from speculation.

The second is that there is that there is no real demand for what business is making. The people with money to spend – the more elderly – are saving more precisely because that is the case.

Third, increased inequality because the wealthier are saving more has reduced the multiplier effect on investment – and so has reduced the incentive to do it.

Even negative real interest rates did not induce businesses to spend on investment. Why Bailey now thinks artificially high positive interest rates, set with the deliberate aim of deflating the market in real goods and services, will achieve that outcome is hard to imagine.

Bailey’s argument is that getting older people back to work will apparently solve this problem. Again, when he also thinks that they have the means not to do so, how this makes sense is not at all clear. Indeed, how he even makes the leap from one position to the other – except by saying that this is where the growth potential in the economy is – is hard to fathom.

Bailey concluded saying war has hit us hard, as have the terms of trade (call it Brexit). There is a downturn, he says, in income that we have to acknowledge, but despite that he is intent on forcing inflation down by deflating the economy some more. And, he added, he saw no threat from a banking crisis, to which he had not previously referred. These conclusions did not flow from anything he said. I have to conclude that all that came before the conclusion was a vain attempt to justify high interest rates when in reality none could ever be found in the real economy.

So what should he have said? I offer just three of many things that he might have considered.

The first is that inequality needs to be tackled, very urgently. Money has to be given to those who can spend it and be taken away from those who will not. The distortionary effects of excess savings need to be addressed.

Second, markets are out of ideas because overall people know we do not need more ‘stuff’. What we need is sustainability. It is the exact opposite of more uselessly differentiated products only capable of being sold on the back of massive advertising campaigns that create feelings of dissatisfaction which the products they are promoting cannot dispel because they meet no known human need.

Third, what we need instead is more public services. The way to deliver growth is to supply what people really want, which is an improved NHS, better education, social care and justice, and all from people paid fairly to deliver those things. He is wrong to look to the market for solutions in other words: what we have is a shortfall in state supply in the UK.

Bailey got nowhere near this. It shows how wrong it is to put monetary policy in the hands of such a person and his acolytes: they have no clue about economics, the real world or what is required. Living in their own very comfortable bubbles guarantees that. All they can do is make up falsehoods to justify what they are doing, and as this speech showed, Bailey is not even very good at that.